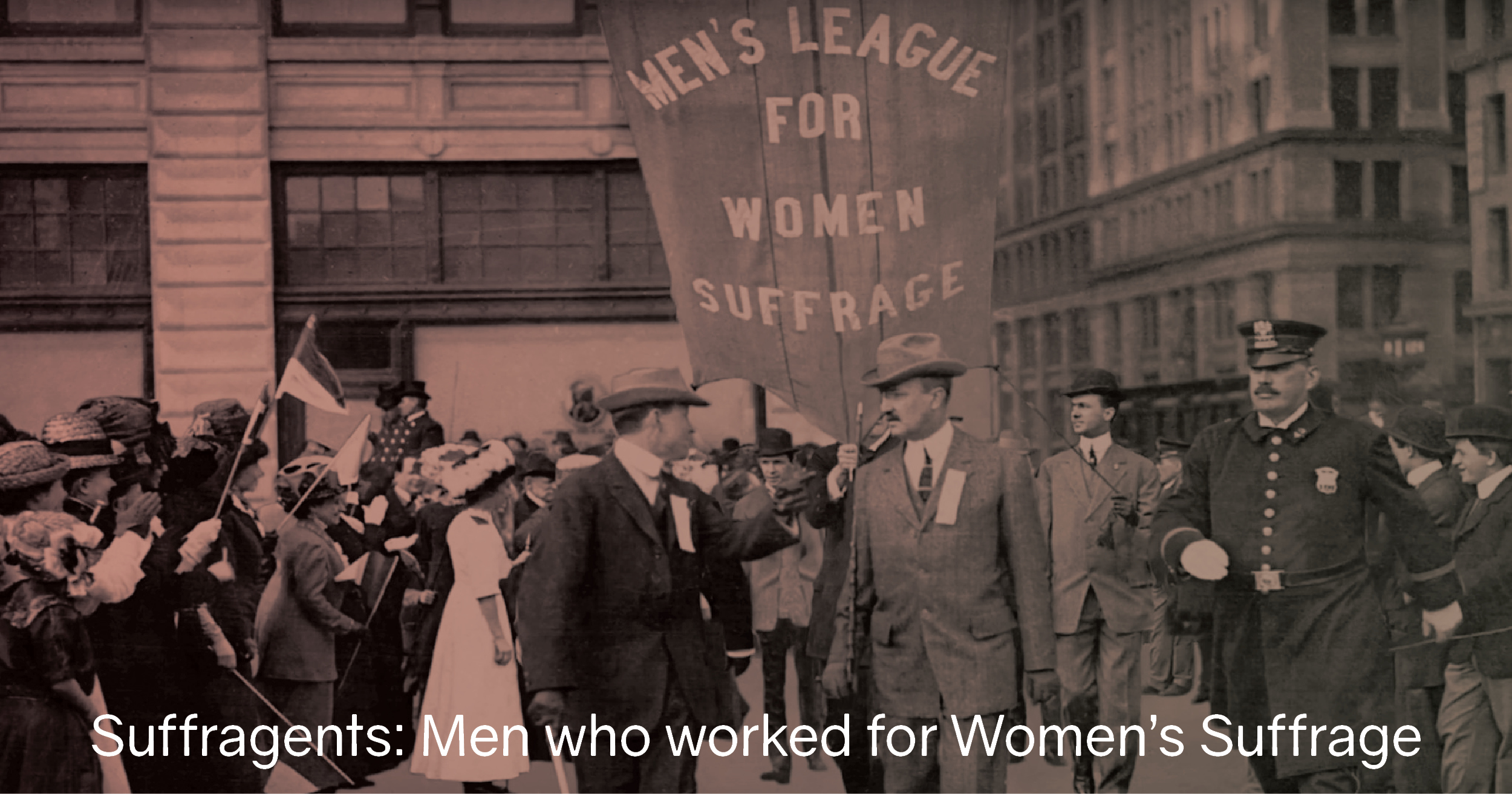

Surprising to some, many of the suffragists’ strongest supporters were their husbands, fathers, brothers, uncles, and other men. There were men throughout the country who were themselves suffragists and who lent their support to advancing the women’s cause.

Showing family influence, many young female suffragists were inspired to take action in the political arena because their fathers were politically active. It is a testimony to their democratic values that a large number of American men consistently supported women’s cause.

There were more than 50 electoral campaigns and in every one, a large number of men — often above 40% — voted in favor of equal suffrage. A majority of male voters in New York, California, and eleven other states actually approved it.

In 1920, after the overwhelmingly male Congress and 36 state legislatures approved it, the 19th Amendment was ratified and rightly hailed as truly a mutual victory.

In The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote, Brooke Kroeger examines the critical role that men played in the women’s suffrage movement through the creation and mobilization of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage. In her work, Kroeger argues that the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement “used” men to gain voting rights during the 1917 state suffrage campaign in New York. From 1908 to 1920, the New York Men’s League hosted fundraisers, participated in marches, gave public speeches, and lobbied government officials for the cause. According to Kroeger, the Men’s League was a “momentous, yet subtly managed development in the suffrage movement’s seventh decade” (p. 1). While Suffragents focuses exclusively on the New York branch of the Men’s League, Kroeger acknowledges that the organization was much larger in scope and created a national network of prominent men who advocated for suffrage through their public presence, such as socialist Max Eastman, muckraker Upton Sinclair, historian Charles Beard, and financier James Lees Laidlaw. However, Kroeger asserts that one of the unique aspects of the Men’s League was that the men were subordinate to the women and their agenda was largely guided by women leaders of the movement.

In The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote, Brooke Kroeger examines the critical role that men played in the women’s suffrage movement through the creation and mobilization of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage. In her work, Kroeger argues that the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement “used” men to gain voting rights during the 1917 state suffrage campaign in New York. From 1908 to 1920, the New York Men’s League hosted fundraisers, participated in marches, gave public speeches, and lobbied government officials for the cause. According to Kroeger, the Men’s League was a “momentous, yet subtly managed development in the suffrage movement’s seventh decade” (p. 1). While Suffragents focuses exclusively on the New York branch of the Men’s League, Kroeger acknowledges that the organization was much larger in scope and created a national network of prominent men who advocated for suffrage through their public presence, such as socialist Max Eastman, muckraker Upton Sinclair, historian Charles Beard, and financier James Lees Laidlaw. However, Kroeger asserts that one of the unique aspects of the Men’s League was that the men were subordinate to the women and their agenda was largely guided by women leaders of the movement.

Suffragents is one of the first works to fully examine male involvement in the American suffrage movement, an area of historical study that has long been ignored by suffrage historians.

Suffragents to Celebrate!

Thomas Paine (1737–1809) was was an English-born American political activist, philosopher, political theorist, and revolutionary. He authored the two most influential pamphlets at the start of the American Revolution and inspired the patriots in 1776 to declare independence from Great Britain.

He also wrote “An Occasional Letter on the Female Sex,” published anonymously under his editorship in the Pennsylvania Magazine in August 1775. It features the “Letter,” which argues that the oppression of women is universal and pleads for the better treatment of women.

In 1836, Thomas Herttell (1771–1849), a 65-year-old reformist lawyer and state legislator from New York City who advocated for universal suffrage, introduced a bill into the New York legislature to protect the property rights of women, who by law lost that right to their husbands upon marrying, writing: “It is doubtless obvious to those who have paid due attention to the provisions of this bill that its primary principle is to preserve to married women the title, possession, and control of their estate, both real and personal after as before marriage; and that no part of it shall innure to their husbands, solely by the virtue of their marriage.”

Susan B. Anthony was born on February 15, 1820, in Adams, Massachusetts. Her father, Daniel Anthony (1794–1862), was an important role-model for his famous daughter, and provided her with financial and moral support in her work for abolitionism and women’s rights.

Samuel Joseph May (1797–1871) was an American reformer during the nineteenth century, and championed multiple reform movements including education, women’s rights, and abolition of slavery. May argued on behalf of all working people that the rights of humanity were more important than the rights of property, and advocated for minimum wages and legal limitations on the amassing of wealth.

George Washington Julian (1817–1899) had espoused the cause of women’s suffrage as early as 1847. As Julian explained in his memoirs, “the subject was first brought to my attention in a brief chapter on ‘the political non-existence of woman,’ in Miss [Harriett] Martineau’s book on ‘Society In America,’ which I read in 1847. She there pithily states the substance of all that has since been said respecting the logic of woman’s right to the ballot, and finding myself unable to answer it, I accepted it. On recently referring to this chapter I find myself more impressed by its force than when I first read it.”

Julian was also close friends with Lucretia Mott, co-organizer of the Seneca Falls Convention. In 1868 he proposed a constitutional amendment on women’s suffrage, but it was defeated.

Robert Purvis (1810–1898), the patriarch of one the wealthiest and most prominent Black families in Philadelphia, used his considerable wealth to support many progressive causes in addition to abolition. With Lucretia Mott, he supported women’s rights and suffrage. When Mott was president, he was a member of the American Equal Rights Association. Purvis also attended the founding meeting of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association.

In 1848, Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women’s rights convention. Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked the assembly to pass a resolution asking for women’s suffrage. Douglass stood and spoke in favor of women’s suffrage, saying that the world would be a better place if women were involved in the political sphere.

Robert Dale Owen (1801–1877) served in the Indiana House of Representatives from 1835–38 and again from 1851–53. He was instrumental in introducing legislation and argued in support of widows and married women’s property rights. He also proposed laws granting women greater freedom of divorce.

In addition to serving in the state legislature, Owen was elected as a delegate to the Indiana Constitutional Convention in 1850. At the convention, he initiated a proposal to include provisions for women’s property rights in the state constitution. Although it was not approved, this early effort to protect women’s rights led to later laws that were passed to secure women’s property, divorce, and voting rights.

In 1853, Rev. Luther Lee (1800–1889) ordained Miss Antoinette Brown, one of the first women to be ordained in the Congregational church. To recognize this historical event, Rev. Lee gave a special sermon, stating in his introduction, “The ordination of a female, or the setting apart of a female to the work of the Christian ministry, is, to say the least, a novel transaction, in this land and age. It cannot fail to call forth many remarks, and will, no doubt, provoke many censures. As I have been called upon to deliver the discourse on the occasion, I should deem it out of place, tame and cowardly, for me to deliver an ordinary sermon setting forth the duties and responsibilities of a Christian minister, without taking hold of the peculiarity of the occasion, and vindicating the innovation which we this hour make upon the usages of the Christian World.”

Matthew Vassar’s (1792–1868) niece, Lydia Booth, a teacher who ran the “Cottage Hill Seminary” out of a building Vassar owned on Garden Street, encouraged him to establish a women’s college in Poughkeepsie. In January 1861, the New York Legislature passed an act to incorporate Vassar College, one of the first women’s colleges in the U.S. On 26 February 1861, at the Hotel Gregory in Poughkeepsie, Matthew Vassar presented the college’s Board of Trustees with a tin box containing half of his fortune, $408,000 (approximately $9,700,000 in 2008 dollars) and a deed of conveyance for 200 acres of land to establish the campus.

Dr. Peter Wilson (1761–1837), a member of the Cayuga Nation, was the First Native American graduate of Geneva Medical College. He went on to practice medicine, served as an interpreter and was a noted orator. He frequently spoke in front of the New York Historical Society about topics related to Native American issues. In 1866 he spoke in favor of universal suffrage, admonishing the members that Reconstruction was a good opportunity to extend the vote to all Americans.

Parker Pillsbury (1809–1898) was an American minister and advocate for abolition and women’s rights. Pillsbury lectured widely and earned a reputation for successfully dealing with hostile crowds through non-resistance tactics. The American Equal Rights Association was formed by prominent leaders in the anti-slavery and women’s rights movements, such as Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, Frederick Douglass, and Susan B. Anthony, with the goal of bringing together abolitionists and women’s rights advocates in the fight for universal suffrage, and Pillsbury joined their effort.

In January 1878, Sen. Aaron A. Sargent (1827–1887) introduced a joint resolution proposing an amendment to to the United States Constitution. Sadly, it failed, but it contained the 29 words that would later become the 19th Amendment. Sargent’s wife, Ellen Clark Sargent, was a leading voting rights advocate and a friend of such suffrage leaders as Susan B. Anthony. His bill calling for the amendment would be introduced again and again, unsuccessfully, each year for the next forty years.

Arthur Caswell Parker (1881–1955) was an anthropologist, historian, and museum pioneer, who wrote about the history and culture of the Iroquois People, including the role of Haudenosaunee women in political decisions. As director of the Rochester Museum of Arts and Science, he gave a brief argument for modern American women to consider in 1909: “…that the red woman that lived in New York state five hundred years ago had far more political rights and enjoyed a much wider liberty than the twentieth century woman…” In 1909, he wrote an opinion piece titled “Woman’s Rights in America Five Hundred Years Ago,” which appeared in the Albany Press on April 11, 1909.

Max Eastman (1883–1969) was a prominent socialist whose parents were both ordained ministers. In 1910 he helped found the Men’s Equal Suffrage League. Eastman was President of the Men’s Equal Suffrage League of New York State when he delivered his talk at Bryn Mawr in 1913, titled “Woman Suffrage and Why I Believe in It.” The Lantern reported that “the result of his speech was a number of converts to woman suffrage.” His sister, Crystal Eastman, was a prominent member of the Congressional Union and the National Woman’s Party.

California banker John Hyde Braly (1839–1923) attended a meeting of suffragists in Los Angeles and was immediately drawn to their cause, freely using his own money and social capital to spread the word for suffrage. When he wrote his memoirs, Memory Pictures, he dedicated an entire chapter to his work in the suffrage movement, claiming it was the “crowing work of his long life.”

Eugene V. Debs (1855–1926) was serving a 10-year sentence in prison during the 1920 election, but his decades-long commitment to women’s rights helped him earn nearly 1 million votes, a record for the Socialist Party candidates that still stands today.

Debs first met Susan B. Anthony in 1879, when he invited her speak in his hometown of Terre Haute, Indiana. His friendship with Ida Husted Harper was also quite formative in his early years as a writer and socialist thinker, and he always included full equality for women in his platform.

Howard Cosell (1918– 1995) was a sports broadcaster with strong opinions, and a national audience. His friendship with boxing great Muhammad Ali is well known in sporting history. But he was also the commentator for the “Battle of the Sexes” tennis matches between Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs.

In the October 1975 issue of Ms. Magazine, Cosell wrote, “It’s long since past time in this society that women were treated coequally with men and I don’t think they are in many important areas of human existence.”

Actor and author Alan Alda (1936–) may be most well known as the boozing, womanizing Dr. Hawkeye Pierce from M*A*S*H, but in his life off screen he has been a long-time advocate for women’s rights, lending his time and energy to the push for the Equal Rights Amendment during the 1970s and early-1980s. He even served as a cochair on the ERA subcommittee for the National Commission on the Observance of the International Women’s Year, established by President Ford in 1975.

Robert P. J. Cooney, Jr. (1950–) is the author of Winning the Vote: The Triumph of the American Woman Suffrage Movement, a widely praised and beautifully illustrated history of this important movement. Director of the Woman Suffrage Media Project since 1993, he has spent years delving deep into the nation’s photographic archives and has also consulted on numerous documentary films, books, and special projects. And he’s a member of the NWHA Board!

In her book The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote, Brooke Kroeger examines the critical role men played in the women’s suffrage movement through the creation and mobilization of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage.

In her book The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote, Brooke Kroeger examines the critical role men played in the women’s suffrage movement through the creation and mobilization of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage.

From 1908 to 1920, the New York Men’s League hosted fundraisers, participated in marches, gave public speeches, and lobbied government officials for the cause. According to Kroeger, the Men’s League was a “momentous, yet subtly managed development in the suffrage movement’s seventh decade.”

While The Suffragents focuses exclusively on the New York branch of the Men’s League, Kroeger acknowledges that the organization was much larger in scope and created a national network of prominent men who advocated for suffrage through their public presence, such as socialist Max Eastman, muckraker Upton Sinclair, historian Charles Beard, and financier James Lees Laidlaw. However, Kroeger asserts that one of the unique aspects of the Men’s League was that the men were subordinate to the women and their agenda was largely guided by women leaders of the movement.

Support the NWHA and learn more about the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage by buying The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote:

The National Women’s History Alliance uses affiliate links for Amazon and Bookshop. At no additional cost to you, when you click the links above we will earn a small commission for each purchase you make.