It was the late 1970s. Molly Murphy MacGregor, a graduate student at Sonoma State University (SSU), taught a lively class on Women and Social Change at Santa Rosa Junior College (SRJC) Petaluma campus.

Momentum to study, uplift and celebrate women grew throughout the decade nationally and in Northern California; students and faculty at SSU pushed to create a women’s studies major in 1972, the Supreme Court passed Roe v. Wade in 1973 and Dr. Angela Davis rose to international renown as a professor, author and revolutionary fighting for women’s rights and Black liberation.

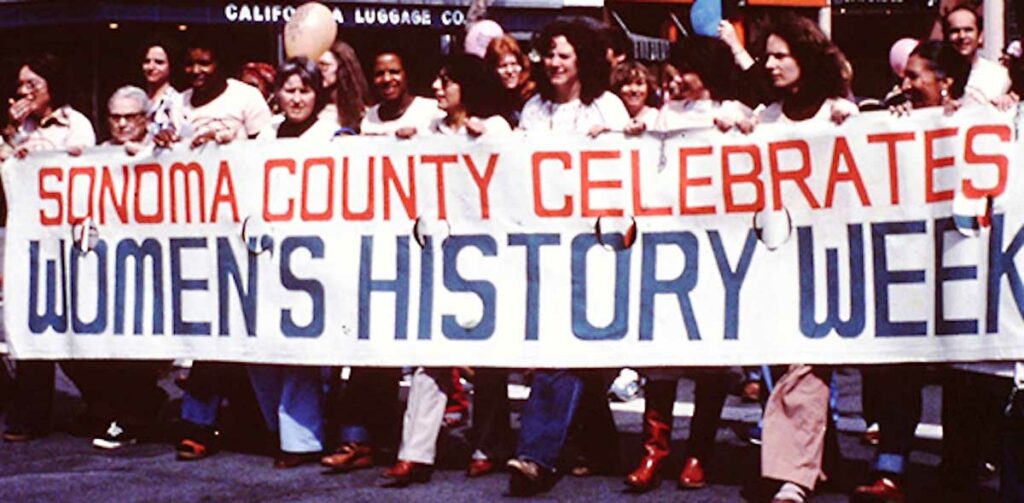

MacGregor and a group of local women would go on to create the first Women’s History Week in Sonoma County schools in 1978. Two years later, President Jimmy Carter called for Women’s History Week to be recognized nationally. In 1987, a Congressional resolution established Women’s History Month as a national phenomenon. This year will be MacGregor’s 43rd and final year as executive director of the National Women’s History Alliance (NWHA).

She didn’t grow up planning to dedicate her life to teaching women’s history. Her conversion, as she calls it, took place while she was a high school teacher. When a student asked her about the women’s movement, MacGregor found herself speechless. At that moment, she recognized how little she knew and taught about women. That recognition proved pivotal, changing the course of MacGregor’s life.

At SRJC, many of MacGregor’s students were young mothers returning to school. A few of these parents went to their childrens’ grade school libraries to check out books about women’s history. According to MacGregor, they found almost nothing—five to seven books, which hadn’t been checked out for years.

“We knew they hadn’t been checked out because teachers hadn’t assigned them. And teachers hadn’t assigned them because teachers were never taught women’s history. All of us teach what we know,” MacGregor says.

Galvanized by a shared desire to provide the curriculum schools lacked, MacGregor and her students approached the Sonoma County Office of Education and asked to put Women’s History Week on school calendars. Soon after, MacGregor was among a group of women who formed the Education Task Force of the Sonoma County Commission on the Status of Women.

MacGregor says, “We would provide teachers with resources and resource women to come in and talk during that week. Our goal was always to empower teachers and educate them as much as we could.”

To create women’s history curricula, the women had to rely on source materials that underscored how dire the need for women’s history truly was. “When we started writing all the biographies we wrote, the most prestigious [source material] we read would make you think all these women had sprung from the head of Zeus—all you heard about were their fathers,” MacGregor exclaims.

Over the past 43 years, MacGregor says the country’s collective awareness of women has grown exponentially. Much of the misogyny was not deliberate, according to her.

“There was extraordinary unconscious bias against women. We had to really prove that women had been great artists and scientists….Going back to any culture at any time, you’ll find out that women were substantial in every single aspect of the development of history, but people did not realize,” she says.

MacGregor attributes the national success of Women’s History Month to bipartisan support. In 1981, Reps. Orrin Hatch and Barbara Mikulski co-sponsored the first joint Congressional resolution proclaiming Women’s History Week.

Yet the need for bipartisan support also kept MacGregor and other lesbians in the movement in the closet about their sexual orientation for decades to come. While supportive of women’s history curriculum, Hatch opposed LGBTQ+ rights bills until at least 2012.

“Was there lesbian energy behind our work? You betcha,” says MacGregor.

She continues, “Lesbians were among the first people to understand that women were important. Women’s studies was always a women-loving-women supportive space.”

Each year, the NWHA chooses a theme for Women’s History Month. In their magazine, Women’s History, MacGregor writes, “Throughout 2023, ‘Celebrating Women Who Tell Our Stories,’ encourages recognition of women past and present who have been active in all forms of media and storytelling, including print, radio, TV, stage, screen, blogs, podcasts and more.”

Articles within the issue highlight women storytellers who amplify stories from within their own communities. The magazine spotlights Indigenous women storytellers who upheld their cultural traditions even when the U.S. outlawed storytelling in the Code of Indian Offenses in the 1880s.

In the article, “Telling Black Women’s Stories,” Cynthia Denise Robinson Smith writes, “Storytelling is important and dates to slavery. Blacks were forbidden to read and write. It was illegal and could also be fatal. The only avenue available to them was talking about it.”

MacGregor says reading the stories of countless women of color throughout history has shaped and expanded her. “I grew up with a terrible amount of white privilege, and I was so under-educated about it. I’m 77 now, and I say that means I’ve had a lifetime to unlearn some of the lies I was told growing up,” she says.

Although she is heartened by much of the activism and care she sees locally, MacGregor feels there’s a lot to fight for in the U.S. right now. She is deeply shaken about Roe v. Wade being overturned, calls to ban books and attacks on trans children.

“It’s facism that we’re facing,” MacGregor says. Then she asks, “Who are these people that are so afraid of learning about the complexities of our history?”

Despite her many grave concerns, MacGregor is confident that younger generations have the numbers and power to fight.

As quickly as she gets fired up about what worries her, MacGregor becomes effervescent about what makes her hopeful. Last week, women in Vietnam, Spain and Germany called her to ask advice on how to start a Women’s History Week.

“I know you’re writing about me, but I can’t tell you how important it is to recognize all the women who founded this with me and the hundreds of thousands of women since,” MacGregor says.

***

Continuing Education: In celebration of local activists uplifting the history of women in and around Sonoma County, the author of this article recommends:

- The Women & Gender Studies Lecture Series at SSU

- The Lesbian Archives of Sonoma County collection, housed at the GLBT Historical Society

- The Sonoma County Black Forum

- Sonoma County Commission on the Status of Women

- The Louise Lawrence Transgender Archive in Vallejo

- Oral histories of members of the Movimiento Cultural de la Unión Indigena

- Sonoma County LGBTQI History Timeline